Affordances Defined and Perceived

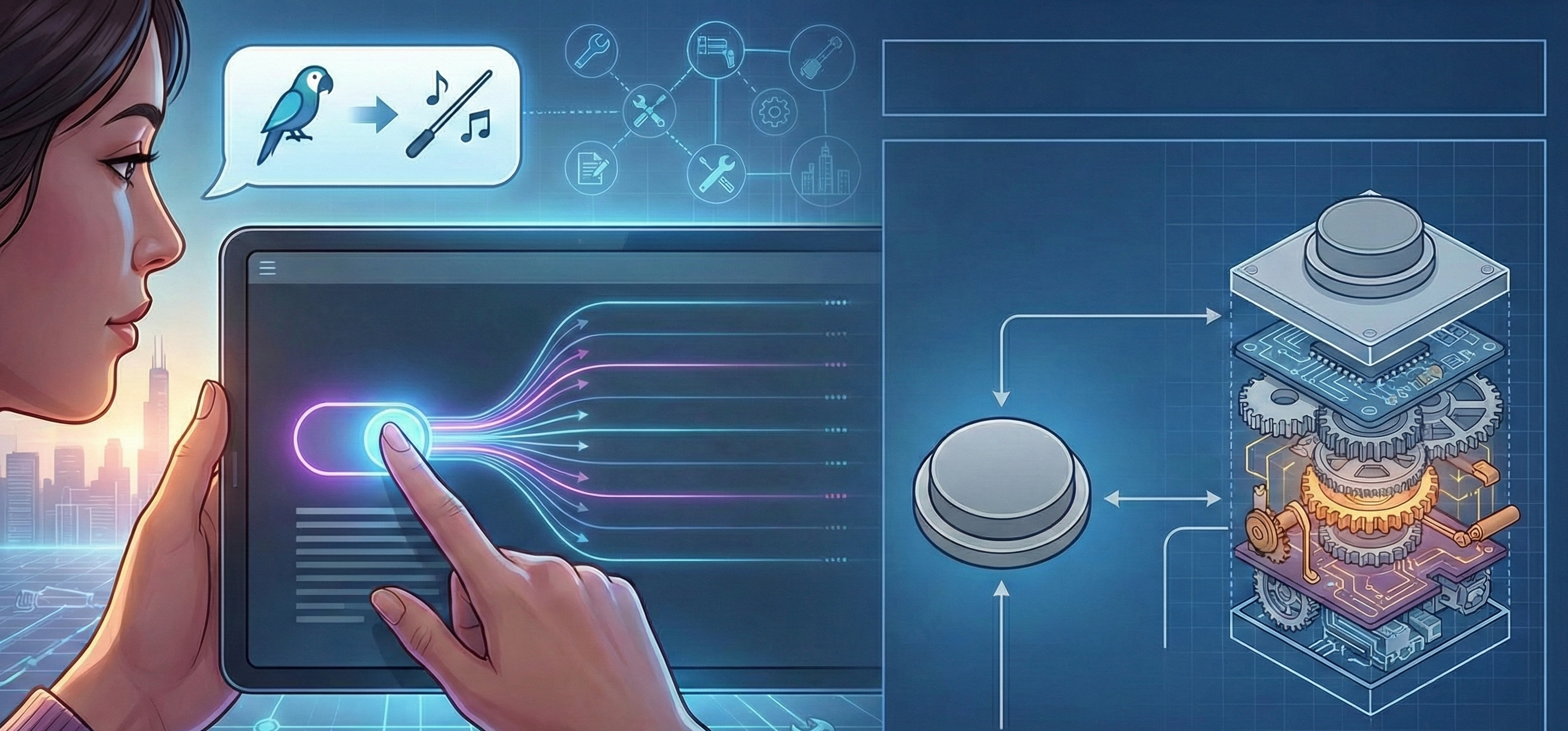

On Thursday morning, Samantha opened the “prompt lab” and noticed something she hadn’t seen the week before. A tiny toggle read “ground with live context.” She clicked it. Instantly, the model’s ideas stopped sounding like generic lifestyle copy and started referencing the day’s weather in Chicago and a surge in searches for “quiet mornings.” The work felt less like talking to a clever parrot and more like conducting with a new instrument. The new interface in the tool had revealed a new capability that Samantha could then explore.

That’s the heart of this section: the ways tools invite new actions. Not just what they can do in principle, but what they make easy to do in practice—their affordances. We’ll get precise about what that word means, how our perception of affordances shapes behavior, why the mind you bring to work is actually a system (brains + bodies + tools), and how stacked tools create unexpected capabilities. We’ll zoom out to the city—the infrastructure that changes how whole communities think and live—and we’ll face the shadow side: skill polarization and tool overwhelm. Samantha will be our thread, because her week is where these abstractions turn into choices.

Affordances Defined and Perceived: How We See Possibilities

What is an “affordance”? Researcher James Gibson coined the term affordance to name the action possibilities which an environment offers to an animal, relative to that animal’s capabilities. He writes, “The affordances of the environment are what it offers the animal, what it provides or furnishes, either for good or ill.”

Crucially, affordances in Gibson’s sense exist whether or not they are noticed; they are relational (between environment and actor) and cut across the subjective neither purely “in the head” nor just a physical property.

In Don Norman’s Design or Everyday Things he borrowed the term affordances to talk about what users think they can do with an artifact which he called perceived affordances. He later clarified that in interfaces, the designer’s job is to shape what people perceive as possible more than what is physically possible.

An affordance is both what an environment offers you and how it is presented so that you can understand its possibilities. A handle affords pulling; a button affords pressing. In digital work, the “handles” are often invisible: a gray token that means “drag me to filter,” a placeholder that implies “type a question here,” a toggle that silently says “turn on context.” We don’t act on the world as it is. We act on the world as we perceive it.

On November 30, 2022, OpenAI first introduced a conversational interface for generative AI (ChatGPT). It was not the first time that OpenAI had provided access to their large language models (LLMs). But previously access had been through an “application programming interface” (API) which while convenient to software developers, was entirely inaccessible to the average user. The introduction of a conversational interface changed that and suddenly made LLMs accessible to anyone with a web browser. The challenge though in the way that OpenAI presented generative AI is that it created a narrow perception of this technology and encouraged people to interact with it in this narrow way, a chatbot.

Understanding and fully taking advantage of this new affordance requires going beyond the surface perception. Here is a useful structure for thinking about any affordance:

- Structural affordances (what’s actually possible): What are all of the things that an LLM is capable of when configured and presented in different ways?

- Signified affordances (what’s advertised): What are the limitations that are placed on this structural affordance by the presentation of the LLM?

- Learned affordances (what experience tells you will work): In actually using generative AI tools, how do you learn what is structurally possible even though it is not signified?

A practical rule: when your results feel “flat,” ask whether you’re missing a structural affordance or misreading a signifier. This dropdown controls tone, This inline trace explains why the model chose X over Y, This preview simulates user context. This model is better at one kind of task vs. another model. And constant learning is required because the tools continue to change, so the structural, the signified, and your learned affordances will also keep changing

Three moves to sharpen affordance perception:

Use a verb to name the affordance. “I’m trying to ground / constrain / branch / score.” Verbs clarify which affordance you’re seeking.

Probe the edges. If you only click what’s obvious, you inherit someone else’s workflow. Touch everything (safely). You’re mapping a territory.

Surface signifiers. Nudge the tool to show its invitations: turn on traces, labels, previews, examples. Ask colleagues to narrate clicks you missed.

Generative AI is so broad and deep that we have to expand our affordance literacy. Once we do so we can teach others to see the right levers faster, which multiplies everyone’s learning.