Cities as Affordance Fields

What does it mean to say that “cities are affordance fields?” Cities are dense layers of physical, social, and digital infrastructure that present structural and perceived affordances. They shape our cognition, our understanding of what is possible. Cities make some actions obvious, some experiments cheap, some connections more likely. In a world where generative AI is rewiring the way we work, learn, and relate to one another, cities remain the place where new patterns get tested first, refined fastest, and made real for the most people.

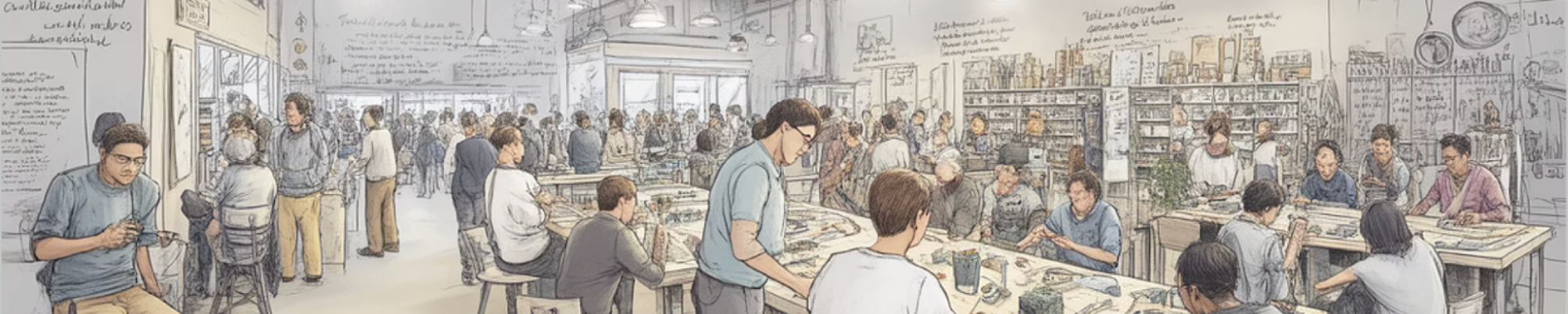

This density of human connections enables us to learn from one another in a lower stakes environment than the office and makes knowledge more accessible to everyone. Imagine a volunteer at the local library who helps a bakery owner turn a grease-stained recipe journal into a searchable, shareable archive for customers with dietary needs. They photograph each page, use an AI tool to transcribe and tag ingredients, and then build a simple web page where customers can filter by “gluten-free,” “nut-free,” or “low sugar.” And the baker leaves with a website but more importantly with a mental model of the capabilities of generative AI.

Community colleges can offer evening classes on data literacy. People who’ve been locked out of tech skills by time, money, and commuting now can have a path to learning. The syllabus would include not only spreadsheets and SQL, but also “How to ask better questions of AI” and “How to check AI answers against reality.” The class would become a weekly ritual where people swap stories of experiments gone wrong and right, building collective knowledge of AI use.

Each of these is an affordance made public: bandwidth, compute, coaching, credentialing, time.

A city that offers free Wi-Fi, quiet rooms, and AI coaching in its libraries changes who can experiment with new tools. A transit system that runs late enough to get you to that 8–10 p.m. class changes who can re-skill while keeping a day job. Zoning laws that allow flexible use of storefronts and warehouses create room for hackerspaces, maker labs, and pop-up AI studios. We need the norms to be “we help each other learn this stuff,” “we don’t shame beginners,” “we share our prompts” and through this can turn individual’s fear into collective curiosity.

When an environment raises or lowers those frictions, who adapts changes, not just how fast.

Historically, cities have always played this role. Guild halls and coffeehouses, salons and stock exchanges, universities and factories were each a piece of infrastructure that made new combinations of ideas and people easier. The printing press made a difference in the quantity of information available for distribution; the printers, writers, merchants, and readers crammed into a few city blocks, could then easily copy, distribute, argue, revise. It isn’t about the physical atoms of a printed page, it is about the community of people who gather around the knowledge. So the same is happening now with digital generative AI, only the tools are in the cloud and in our pockets, while the learning still happens around tables, screens, and shared problems.

Company’s can mirror some of these advantages of density, when the norms are similarly welcoming. Telling employees “you’ll be fired if you don’t use AI” is the most likely way to scare good people to seek employment elsewhere. If a company can create the same "we help each other learn this stuff,” “we don’t shame beginners,” “we share our prompts” then through this a company can also turn employee’s fear into collective curiosity.

Suggestions: add “office hours” with data science and design partners, but held them in open spaces and invited anyone from operations to HR and bring real problems to the group. Write plain-language guides that show concrete examples per role instead of abstract principles, and then print them, post them, and turn them into short lunch-and-learn sessions. Lend exploration time to teams with the least exposure to AI, not just the loudest volunteers.

Perhaps most importantly, change the social topology: create cross-functional “prompt circles” where people met biweekly to share what they were trying, what broke, and what saved time. Over a few months, your company will develop its own informal map of what AI was good for in that specific context. The result will be more output but also wider participation in the new way of working.

This is the deeper role of cities in the age of generative AI: they are where affordances get composed into systems. A single tool is just potential. But put that tool in a specific neighborhood (even if that “neighborhood” is a company), with a certain mix of languages, industries, and histories, and it turns into something else: a translation hub for immigrants, a pattern-finder for local health data, a storytelling engine for community histories.

The same technology looks different in different affordance fields:

• In a city where the main public-facing AI infrastructure is a handful of corporate training sessions, people learn to see AI as something done to them.

• In a city where libraries, rec centers, co-working spaces, and colleges all host experiments, people learn to see AI as something they can do with others.

The distribution of these affordances matters for our economic, political, social, and cultural future.

Economically, cities that lower the cost of experimenting with AI for small businesses, gig workers, and nonprofits will see more bottom-up innovation, not just top-down deployments from large enterprises.

Politically, cities that help residents see and scrutinize how AI is used in public services—benefits processing, policing, education—will build more informed civic oversight. Public workshops on “how this system works and how to challenge it” are as important as the systems themselves.

Socially, cities that support spaces where people learn together—community labs, meetups, shared studios—will soften the isolation that often accompanies rapid technological change. Learning becomes a social act, not a private panic.

Culturally, cities that invite artists, educators, and youth into the AI conversation will generate new stories, metaphors, and rituals for how to live well with these tools, not just how to optimize them.

All of this points back to a simple but hard design question for leaders:

What does our environment make easy and for whom?

If you run a city, that question points at zoning, transit, digital infrastructure, library budgets, school partnerships, support for community colleges, and the small grants that keep neighborhood labs alive.

If you run a company, that question points at calendars, coaching, access to tools, psychological safety, and who gets first crack at experimentation. Do front-line workers have a way to try AI on their tasks, or is everything routed through a central innovation team? Can people say “I don’t know how to do this yet” without penalty?

If you run a school or a nonprofit, that question points at how you blend curriculum with lived problems, and whether community members can bring their own questions to the table. Is AI something students learn about in isolation, or something they use to work on issues they care about locally?

Generative AI will keep advancing. Models will get faster, cheaper, more capable. But the real leverage isn’t just in the models; it’s in the environments we build around them. Cities, with their density of people, problems, and places, are uniquely positioned to be the world’s adaptive nervous system sensing where new capabilities are needed, routing attention and resources, and helping people learn together at human scale.

Journal questions:

Where, in my part of the city or my organization, could one small new affordance (a weekly AI clinic, a shared lab, a clearer guide, an hour of protected exploration time) change who gets to adapt next?

Because in the end, the future doesn’t just arrive. It’s learned into existence, block by block, room by room, prompt by prompt.