Processing the Shock of AI

Coping can carry you through the first part of the AI transition. But coping only gets you so far. To keep going, you have to learn thriving, a different kind of motion: not fighting change, not fleeing it, but meeting it with all of you, not just your intellect but your nervous system and values as well. This section is about that turn. It’s where I will talk about the inner weather of change and make a practical case for psychological flexibility as a trainable meta-skill for adaptation.

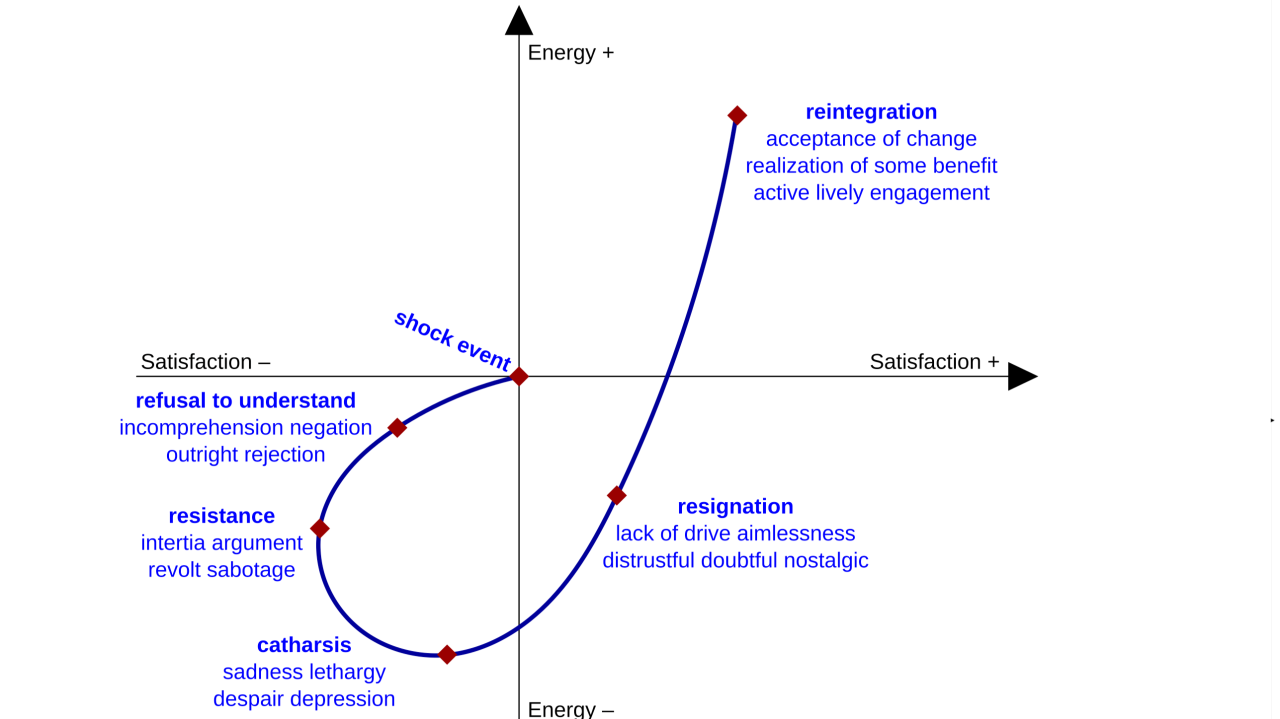

Most people do not have a fixed view when change happens but go through a personal journey in responding to the “shock of the new.” This is as true of other changes in our lives as it is about the set of ideas that AI has introduced. The Kübler-Ross stages of grief were developed to describe how terminally ill patients can come to accept their own mortality, moving from denial through a number of stages to ultimately coming to peace with the inevitable. The model is really designed to describe the patients themselves, but a similar process is experienced by the family and friends of such patients, and others have sought to modify the journey of the description to reflect what happens for such people after their loved one has passed on. The important difference is that the healthy outcome should be “reintegration” with society once that acceptance has let to the inevitable.

You might be wondering why I am taking about terminally ill patients when the subject at hand is how professionals respond to organizational change. In my view one of the challenges we face in transformation even in a professional context is the sense of loss that we can feel for the world we know and take comfort in, the loss of tasks and competencies that define who we are in our work.

In this regard I believe there is a lot to learn from the re-envisioning of the Kubler-Ross model (five stages of grief) by Bertrand Grondin (the image at the top of this article). In Grondin’s revision of a person’s journey he looks at the stages in the context of two dimensions, “satisfaction” and “energy.”

The original model consisted of five stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance (DABDA). There can be loops back to earlier stages, but principally it was envisioned as a linear journey. The Grondin model improves on DABDA when we are thinking of a person’s reaction to a “shock event” such as the impending impact that a new technology has on our ways of defining ourselves, or our society.

While there is a similarity in the early reaction of denial, anger, and bargaining, the good news about this journey is that it can have a positive endpoint. Not acceptance of death, as in the terminally ill patients in the Kubler-Ross journey, but instead the journey moves toward “reintegration” with the potentials of “realization of some benefit” and “active lively engagement” as future mental states. In this the revision of the stages we pass through is better aligned with other kinds of coping than simply grief.

Examining the Grondin more closely an interesting observation about this journey is that the loss of “energy” can create motion back towards positive “satisfaction.” The message here is that acceptance can also bring peace, which can then become the foundation for growth. We will further explore the journey from anger through acceptance, and then on to growth and thriving in this moment of change.